This is based on a talk I once gave to a physics teachers conference to see how far one could get explaining particle physics without using lots of maths and equations but just concepts familiar from A-level physics.

For what it’s worth, the feedback I got afterwards was that it was entertaining but far too difficult. I’d failed dismally. Let’s try again, slowly…

First, what’s a field? For today’s purposes, it’s a numerical quantity which is defined everywhere. A good example (though it’s macroscopic not microscopic) is temperature: There is some T(r,t) which has a value for any r and t, even in places a thermometer couldn’t reach.

Another familiar example is the magnetic field B. This is a vector so it has three components, it makes a compass needle point in a particular direction, and has a strength, which determines whether the needle twists gently or forcefully. In the same way there is an electric field E which pushes charges, with some strength and in some direction.

These have been known since the times of the ancient Greeks and Chinese, and physicists in the 19th century spent a lot of effort investigating them and discovered many laws: Coulomb’s law, the Biot-Savart law… which we now summarise as Maxwell’s Equations for the Electromagnetic field, unifying them. There are 3+3= 6 elements in B and E, but if you write them in terms of potentials (φ and A) that can be reduced to 4, and further algebra exploiting the ambiguity in A reduces this to 3.

Maxwell’s equations say that a changing magnetic field produces an electric field (that’s how generators work) and likewise a changing electric field makes a magnetic field, so it’s not surprising that a bit of algebra (2nd year undergraduate level) shows that the equations have solutions that are waves. These Electromagnetic Waves are familiar to us as radio, microwaves, visible light and so on.

It turns out that these waves can’t have any arbitrary energy, only in quanta of a particular packet size, like lumps of sugar rather than powdered. The packet size depends on the frequency, E=hf, so this lumpiness is unimportant for radio waves, becomes noticeable for visible light (as in the photoelectric effect) and is really significant for gamma rays.

An electromagnetic wave packet has energy hf and momentum h/λ and when it starts doing stuff: colliding with atoms, getting absorbed or emitted, it behaves like a particle does. We call it a photon.

Fields → Equations → Wave solutions →particles

At this point you’re probably expecting me to spring a surprise on you. “That’s the traditional 19th/20th century view of the photon, but now we know it’s something completely different…” No. This is the bottom line. The photon is the quantum of the wave solution of the equations governing the electromagnetic field. Any physicist will agree and accept this statement. (They might want to add some extras, but they would not say it was wrong.)

Now let’s consider electrons. These are blatantly particles, but they can diffract and interfere and their wave properties (frequency and wavelength) are related to their energy and momentum just like the photons’ are. We take the fields → particles pattern but start at the other end, suggesting that there is a field ψ(r,t) which somehow embodies the electron-ness at any point. This will obey some equations which have wavelike solutions, which are quantised and the packets are called electrons. Fine, although it turns out that to make it work ψ(r,t) has to have 4 components, which embody electrons and anti-electrons (positrons) with two spin states, up and down.

From electrons we move to neutrinos, and play the same game. The neutrino looks like a neutral electron, so it also has a 4-component field. Another way of looking at it is to call electrons and neutrinos ‘leptons’ and group them both together in one field with 8 components. We’ll come back to this.

Now let’s look at the up and down quarks. They are a pair like the electron and neutrino, but they also have ‘colour’ which has 3 values, so they get described by 8×3=24 fields. The 24 numbers of quarkness relate to the colour, the spin, whether its u or d, and particle or antiparticle. The way this is done is arbitrary: you could say (1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) gave a red spin-down u quark and (0,1,0,…. ) a green spin-up d quark and so on – or whatever – but whatever system used has always got to have 24 separate numbers.

With 24 quark fields and 8 lepton fields that makes 32. So for the three generations (the c and s quarks with the mu and its neutrino, and the b and t quarks with the tau and its neutrino) that makes 96. (Plus 3 for the photon, don’t forget.)

Going back for a minute to the electron field, the numbers are complex, but the overall phase doesn’t matter, because everything gets squared to give probabilities. We might – it’s a free country – elevate this observation to a rule, and extend it by saying that changing the phase should not affect any results, even if the change is not the same everywhere but a function of space and time. Applying this local gauge invariance principle gives various unbalanced differentials in the electron equations and one is forced to introduce the photon field with balancing variations to cancel them: gauge invariance ‘predicts’ the photon. Maybe this sounds like no big deal. You can just make assumptions and write down the equations for the electron fields and for the photon fields, or you can assume the equations for the electron, assume local gauge invariance and then the electromagnetic force, the photon field, emerges. You can save one set of assumptions, but only at the cost of making another.

But then it turns out you can do the same trick with colour and the strong force. There are 3 colours so a quark colour state can be written as 3 numbers, but whether (1,0,0) corresponds to red or green or blue or some mixture is arbitrary (just as when we draw axes on a two dimensional map and start writing down co-ordinates). We can apply the local gauge invariance argument to colour, and to accommodate it we need new fields. These are like the photon and we call them gluons. Just as charges exchanging photons produce the electromagnetic force, colours exchanging gluons produce the strong force. In some ways gluons are just like photons, but in some ways they are different. One such difference is that they themselves have colour (whereas the photon is, of course, not charged) and there are 8 possible colours. That gives another 24 field components.

Encouraged by this, we can try to explain the weak force as arising from local gauge invariance applied to the electron/neutrino and u/d doublets. We can write an electron and a neutrino as (1,0) and (0,1) or the other way round, and applying local gauge invariance to this ambiguity gives 3 extra fields, call them W. But it doesn’t work. These gauge fields inevitably describe particles of zero (rest) mass. The photon indeed has zero rest mass and so, it turns out, do the gluons. But the particles that give the weak force have masses of many GeV. The ambiguity that reduces the 4 component (φ and A) fields to 3 only works when the particles are massless. In a sensibly-organised universe there would be 9 fields describing 3 massless particles carrying the weak force – and indeed for the first small fraction of a second in the early universe this was the case.

But then the Higgs field got involved. This involves two linked assumptions, one reasonable, one weird. First we suppose that there’s yet another field in the game, call it h for Higgs, a doublet like the electron/neutrino or u/d, and with distinct particles and antiparticles, but zero spin, so it takes 4 more fields. Which is fine – with all these fields/particles around there might as well be one more. Then we suppose that the lowest energy state for this field is not zero, but some finite value. That is odd. If you think of electric or magnetic fields, then the lowest energy state is to have zero field – you have to manipulate charges and currents if you want to make anything interesting happen. And all the other fields behave in the same sensible way: if all the ψ electron fields numbers are zero there are no electrons and no energy. Obvious. But the higgs is different: one of its 4 components has some ground state value, and to increase or decrease it means putting in energy.

There is a loose analogy with water in a fish tank. The universe is full of higgsness, or higgsosity, like the tank is full of water, and to take it away (i.e. for a bubble) needs energy. There is a much better analogy with the magnetic field in a ferromagnet. In its lowest energy state all the molecular dipoles are aligned in some direction, giving a non-zero magnetisation.

This unipresent higgsness makes the 3×3=9 massless W fields and the 4 h fields get mixed up, and what we see are 3×4=12 massive W fields (a mixture of the original W and h s; the neutral W gets mixed up with the photon as well and gets called Z but let’s not worry about that) and one lone h field. Either way, they sum to 13.

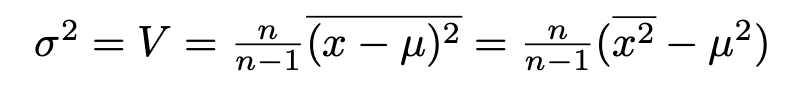

Adding them all up, that’s 96 fields for the quarks and leptons, 24 for the gluons, 3 for the photon, and 13 for the weak + higgs. That makes 136, if I’ve counted correctly. Everywhere, at every point in space-time, there are these 136 quantities, and they develop in time according to a prescribed and established set of rules. Seems complicated? Perhaps it is. Or perhaps it is, in some way we don’t understand yet, actually very simple.

Afterword

What are ‘the laws’? We have Maxwell’s equations for the photon but how do we begin to write down the equations obeyed by all the other 133 fields, which have to describe not just how they behave on their own but how they interact with each other?

We borrow a concept from classical mechanics called the Lagrangian, which goes back to Fermat’s principle of least action. Suppose there is some function L of all the fields and their time-differentials. L(f1,ḟ1,f2,ḟ2,…) and we then require (why not?) that the integral of L is a maximum (or minimum), then the requirement pops out that d/dt(dL/dḟi)=dL/dfi, for all i, and those are the required equations. If you buy into this, the question ‘What are the equations?’ becomes ‘What is the Lagrangian function?’ which is still wide open, but not quite so wide. We now think we know the answer: this is “The Standard Model” and bits of it appear from time to time on mugs and T shirts. It describes the behaviour of everything in the universe (except gravity, which we don’t talk about) and can be written on the back of an envelope, if the envelope is large enough. A4 will do.

Post-afterword

I don’t think there’s anything wrong in the above, but I’m aware that there’s an awful lot left out. Where do these numbers like 3 and 8 come from? What about parity violation? And Majorana neutrinos? And flavour changing in the weak interaction? I know, I know… The truth, nothing but the truth, and though not the whole truth, a large enough chunk of it for one session.

So going back to the experiment, the probability that random background would give a signal like this may be 1 in 20,000 but that’s not the probability that this signal was produced by random background: that also depends on the probabilities we assign to the mundane random background or the exotic axion. Despite this 1 in 20,000 figure I very much doubt that you’d find a particle physicist outside the Xenon1T collaboration who’d give you as much as even odds on the axion theory turning out to be the right one. (Possibly also inside the collaboration, but it’s not polite to ask.)

So going back to the experiment, the probability that random background would give a signal like this may be 1 in 20,000 but that’s not the probability that this signal was produced by random background: that also depends on the probabilities we assign to the mundane random background or the exotic axion. Despite this 1 in 20,000 figure I very much doubt that you’d find a particle physicist outside the Xenon1T collaboration who’d give you as much as even odds on the axion theory turning out to be the right one. (Possibly also inside the collaboration, but it’s not polite to ask.)